D. Yu1, A. M. Abdelrahman1, B. R. Lowndes1, E. Buckarma2, B. Gas2, D. R. Farley2, M. Hallbeck1,2 1Mayo Clinic,Department Of Health Sciences Research,Rochester, MINNNESOTA, USA 2Mayo Clinic,Department Of Surgery,Rochester, MINNESOTA, USA

Introduction: Surgical simulation is important for training surgical residents, assessing competency, and ensuring patient safety. Understanding the cognitive and physical demands during simulation could aid in evaluating how simulation-based training prepares residents for unknown tasks. The objective of this study is to quantify and compare workload between standard and advanced surgical simulation tasks.

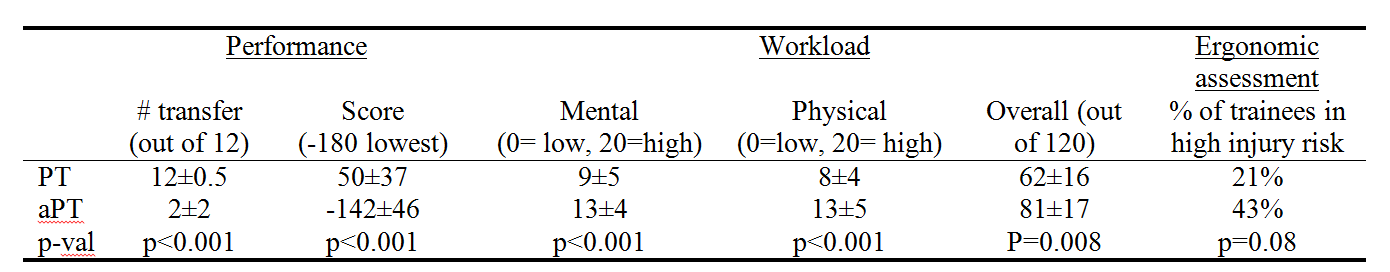

Methods: The study occurred during a semi-annual competitive event at our simulation center. Surgical residents had 3 minutes to complete a well-practiced Peg Transfer Task (PT), then 3 minutes to complete a never-seen before advanced Peg Transfer Task (aPT) mounted on the trainer ceiling. Dependent variables measured during these tasks included performance (time, successful transfers defined as moving a peg from one side to the [max of 12], and scores adjusted for task time and pegs transferred), self-reported workload, and ergonomic risk assessment for musculoskeletal injuries. Workload was measured using the validated NASA-TLX questionnaire with 6 sub-dimensions: mental demands, physical demands, temporal demands, performance, effort, and frustration. Comparison between PT and aPT and relationship among dependent variables were analyzed with paired t-tests, correlations, and regressions at α=0.05.

Results:All 28 surgical residents performed better on PT than aPT (Table), and those who performed better in PT performed better in aPT (ρ=0.54, p=0.003). aPT was significantly more demanding for every workload sub-dimension (Table) except for temporal demand and performance. 21% (PT) and 43% (aPT) of trainees performed tasks in postures requiring immediately action for preventing injuries. Performance (scores and pegs transferred) was negatively correlated (ρ=-0.28 to –0.48, p=0.001-0.036) with every workload sub-dimension except for temporal demand and effort (p>0.05). Regression analysis adjusting for task (PT or aPT) found that perceived performance (β= -0.11, p=0.001) was associated with pegs transferred and effort was associated with task time (β= -2.1, p=0.028). Ergonomic risk scores were positively correlated with frustration and overall workload (ρ=0.37 and 0.29, p=0.006 and 0.033 respectively). After regression analysis adjusting for task, only frustration was associated with higher ergonomic risk (β= 2.5, p=0.015).

Conclusion:Both the questionnaire and ergonomic assessment tools quantified significant increases in workload and injury risks. Better preparation and training for advanced laparoscopic procedures will be mandatory to improve operative performance and prevent serious physical risk to trainees.