A. Najafian1, E. B. Schneider1, E. C. Wick2, J. K. Canner1, J. Wolf2, S. H. Fang2 1Johns Hopkins University School Of Medicine,Johns Hopkins Surgery Center For Outcomes Research/ Department Of Surgery,Baltimore, MD, USA 2Johns Hopkins University School Of Medicine,Division Of Colorectal Surgery/Department Of Surgery,,Baltimore, MD, USA

Introduction:

Learning curves have been widely used to evaluate the impact of training and experience on performance of a new procedure. However, there are many unmeasurable factors that may influence a learning curve. This study aimed to investigate an approach to the learning curve as an academic institution starts a high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) practice.

Methods:

Following IRB approval, a total of 161 HRAs performed on 103 patients by two surgeons over two years at an academic institution were retrospectively reviewed. The two colorectal surgeons had completed the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) approved colposcopy and HRA course. Anal pap smears were obtained concurrently with each HRA performed and the concordance of HRA and Pap smear was examined, based on both volume and duration of practice.

Results:

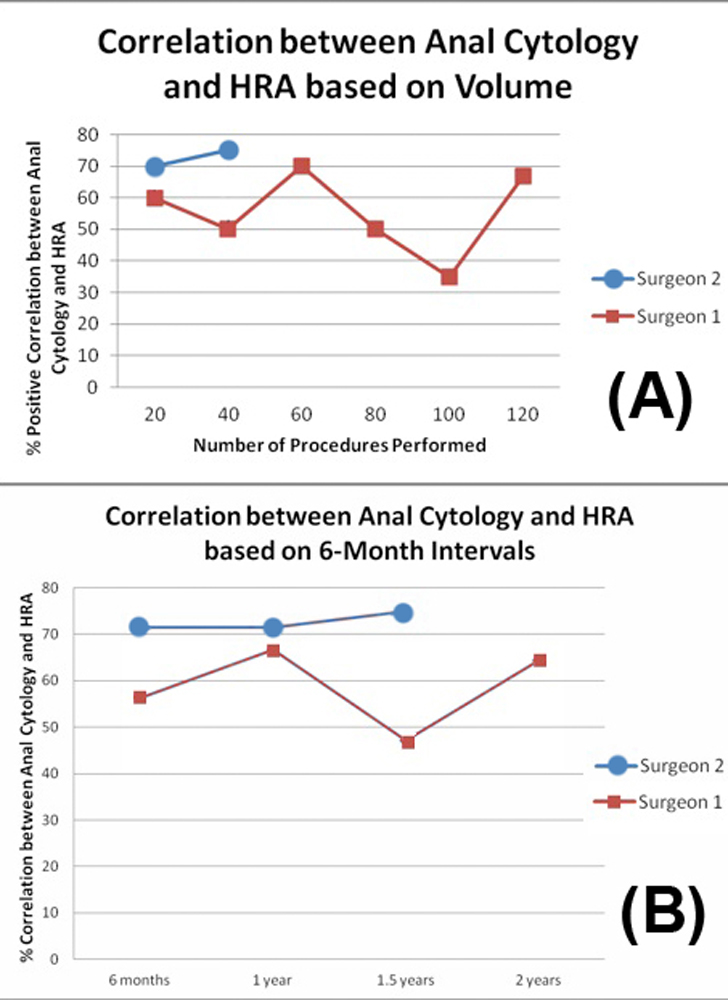

The mean age was 45.5 years (range 23-79) and 70 (68.0%) patients were male. Seventy-eight percent (80/103) of the patients were HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus)-positive and 11% (11/103) of the patients had CD4 counts less than 200. Fifty-three percent of all HRAs performed were positive for anal dysplasia in the presence of abnormal anal cytology. The concordance of anal cytology and HRA improved as case volume increased (from 60% to 67% for surgeon 1 [p=0.24], and from 70% to 75% for surgeon 2 [p=0.72]) (Fig-1-A). Similar results were seen after evaluating the learning curve based on the duration of practice (from 56% to 64% for surgeon 1 [p=0.37], and from 71% to 75% for surgeon 2 [p=0.97]) (Fig-1-B). Interestingly, the changes in concordance were not consistent over time for surgeon 1, who had a peak of 70% vs. a nadir of 35%.

Conclusion:

Although both surgeons demonstrated a non-statistically significant improvement in HRA-cytology concordance over time, the unusual learning curve pattern for surgeon 1 may hint to some challenges that might have impacted the learning curve, including lack of a gold standard for which to compare HRA results and multiple patient-related factors. In order to better evaluate the learning curve, we need to consider all these limitations and be able to control all the potential patient related factors that may impact the surgeon’s performance.