K. N. Partain1, A. Patel2, C. Travers3, C. McCracken3, J. Loewen4, K. Braithwaite4, K. F. Heiss5, M. V. Raval5 1Emory University School Of Medicine,Atlanta, GA, USA 2Emory University,Atlanta, GA, USA 3Emory University School Of Medicine,Department Of Pediatrics, Children’s Healthcare Of Atlanta,Atlanta, GA, USA 4Emory University School Of Medicine,Division Of Pediatric Radiology, Department Of Radiology And Imaging Services, Children’s Healthcare Of Atlanta,Atlanta, GA, USA 5Emory University School Of Medicine,Division Of Pediatric Surgery, Department Of Surgery, Children’s Healthcare Of Atlanta,Atlanta, GA, USA

Introduction: Ultrasound (US) of the right lower quadrant (RLQ) is often the initial imaging modality for evaluation of appendicitis in children. Frequently, the appendix is not fully visualized, and these equivocal US result in subsequent computed tomography scans (CT) or admissions. Our purpose was to determine if the inclusion of secondary signs (SS) observed in equivocal RLQ US reports improves diagnostic accuracy.

Methods: Using retrospective chart review, we identified 825 children (ages 5–18 years) presenting to a pediatric emergency department with concern for appendicitis and a RLQ US. Final US reports were evaluated for primary and SS of appendicitis. The primary sign of appendicitis was a fully visualized appendix (unequivocal US) with a diameter ≥6mm. SS included fluid collections representative of an abscess, significant free fluid, echogenic fat, regional hyperemia, enlarged lymph nodes, hypoperistalsis of adjacent bowel, and appendicoliths. US reports were classified into four categories: 1. Normal; 2. Equivocal without SS; 3. Equivocal with SS; and 4. Appendicitis. Review of operative and pathology reports confirmed appendicitis. Logistic regression models identified which SS were associated with appendicitis, and test characteristics were calculated.

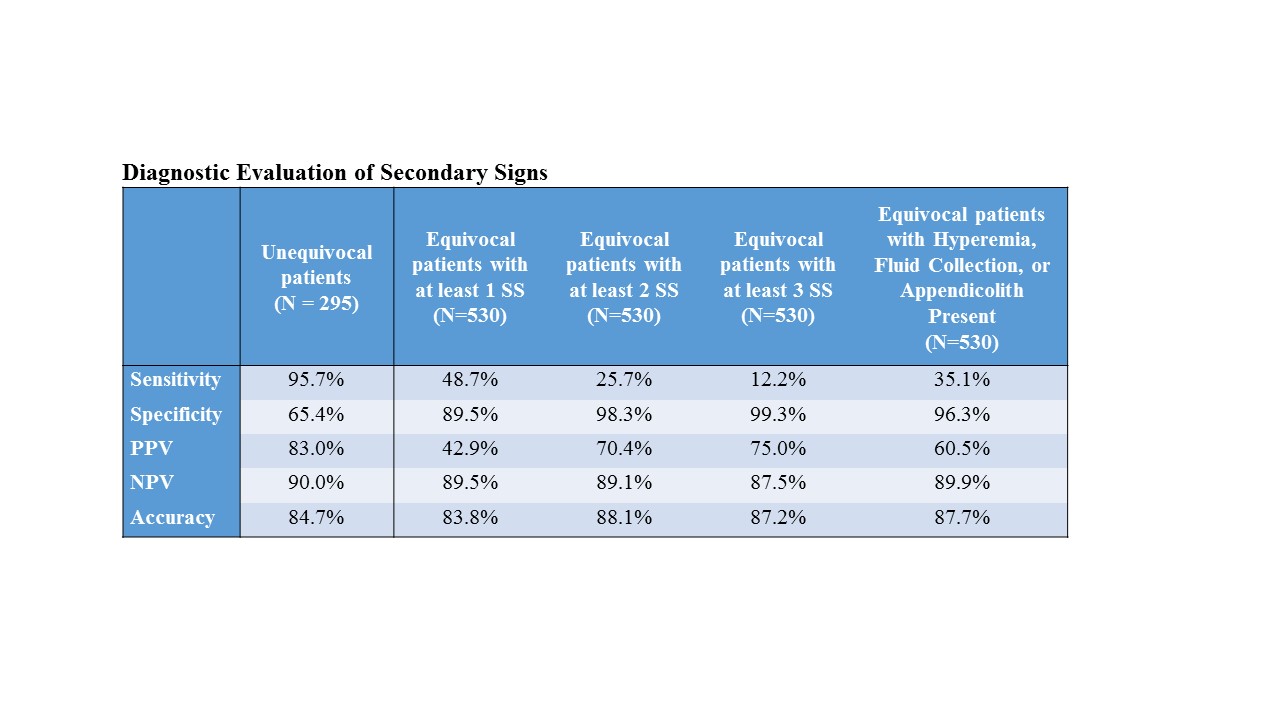

Results: Of the 825 patients, 530 (64%) had equivocal US reports resulting in 114 (22%) CT and 172 (32%) admissions. Of the 114 patients with equivocal US undergoing CT, those with SS were more likely to have appendicitis (48.6% vs 14.6%, p<0.001). Of the 172 patients with equivocal US admitted for observation, those with SS were more likely to have appendicitis (61.0% vs 33.6%, p<0.001). On univariate analyses, all SS were associated with appendicitis except enlarged lymph nodes. After fully adjusting for age, sex, race, and other SS, the SS that were associated with appendicitis included fluid collection (adjusted odds ratio (OR) 13.3, 95% Confidence Interval (95%CI) 2.1-82.8), hyperemia (OR 11.97, 95%CI 1.5 – 95.5), free fluid (OR 9.78, 95%CI 3.8 – 25.4), and appendicolith (OR 7.86, 95%CI 1.7 – 37.2). Wall thickness, hypoperistalsis of adjacent bowel and echogenic fat were not associated with appendicitis in the fully adjusted model. There was no difference in accuracy in the categorization of cases as normal or appendicitis between unequivocal US and equivocal US when SS were used (Table). Equivocal US that included hyperemia, a fluid collection, or an appendicolith had a specificity of 96% and accuracy of 88%.

Conclusion: There is potential to improve the diagnosis of appendicitis. When using SS, equivocal US are as accurate as unequivocal US. Appropriate use of SS can guide clinicians and reduce unnecessary CT and admissions.