O. C. Nwanna-Nzewunwa1, M. Ajiko2, F. Kirya2, J. Epodoi2, F. Kabagenyi2, I. Feldhaus1, C. Juillard1, R. A. Dicker1 1University Of California – San Francisco,Center For Global Surgical Studies,San Francisco, CA, USA 2Soroti Regional Referral Hospital,Surgery,Soroti, SOROTI, Uganda

Introduction: Capacity assessment is an archetypal challenge in surgery. Existing assessment tools use the availability of surgical procedures and resources to identify availability of surgical care. Such methods may fail to capture important information relevant to decision-making and resource allocation among providers, policymakers, and international development partners. This study seeks the relevant information gaps in a tool currently used to assess surgical capacity and explores a mixed methods approach to generate a more complete assessment of hospital surgical capacity.

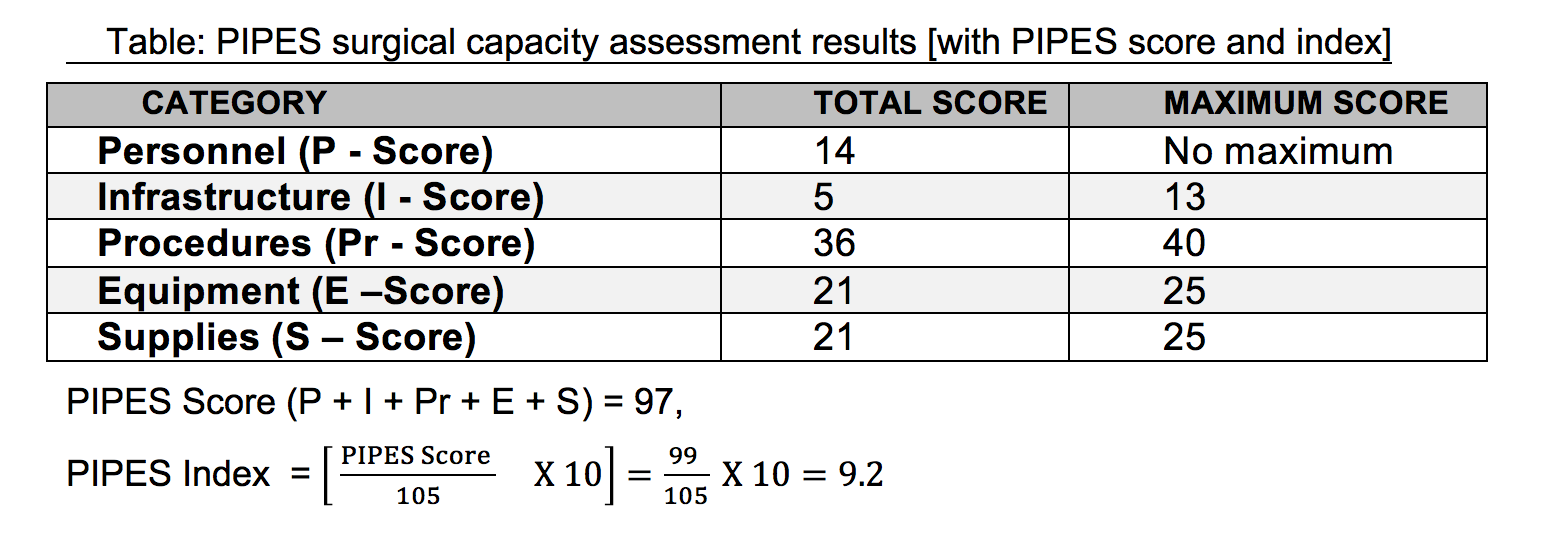

Methods: In June 2015, quantitative and qualitative research activities were conducted to assess emergency surgical care at a Ugandan Regional Referral Hospital. Infrastructure and human resources at a Regional Referral Hospital were assessed using the Surgeons OverSeas’ Personnel, Infrastructure, Procedures, Equipment and Supplies (PIPES) tool, generating a standardized index and score. Thematic analysis was conducted on four semi-structured focus group discussions with 18 purposively sampled providers involved in the process of surgical care delivery. The process of emergency surgical care was directly observed using time-and-motion methodology over 53 consecutive days to produce a process map.

Results: The PIPES tool identified major deficiencies in workforce and infrastructure; but not the cumulative impact of these deficiencies (e.g. lack of physical space) on the timeliness and process of care. The PIPES tool (see table) lacked indices to capture the in-hospital delays; barriers to accessing available procedures; effect of poor remuneration of providers on their availability at work; upshot of the ‘no user fees policy’ on patient throughput and quality of care. These were revealed in focus group discussions, midnight census and process mapping which also provided sociocultural context and the inimical effect of well-intentioned policies on the process of care. The PIPES tool understated the surgical workforce because it did not include orthopedic officers in its personnel assessment; this may misdirect training and capacity building efforts to only physicians or surgeons. The tool did not show the serious impact of the few unavailable procedures on patient throughput and access to care and may misrepresent the availability of services.

Conclusion: There is a need to augment the information obtained from existing surgical care assessment tools. We recommend the use of direct observation of the process of care in combination with qualitative interviews that capture the providers' experience in order to have a robust assessment of the process of surgical care, especially in developing countries where the systems and processes are less well understood.