R. C. Jacobs1, S. Groth1, F. Farjah2, M. A. Wilson3, L. A. Petersen4,5, N. N. Massarweh1,4 1Baylor College Of Medicine,Michael E. DeBakey Department Of Surgery,Houston, TX, USA 2University Of Washington,Division Of Cardiothoracic Surgery,Seattle, WA, USA 3VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System,Department Of Surgery,Pittsburgh, PA, USA 4Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center,VA HSR&D Center For Innovations In Quality, Effectiveness, And Safety,Houston, TX, USA 5Baylor College Of Medicine,Department Of Medicine,Houston, TX, USA

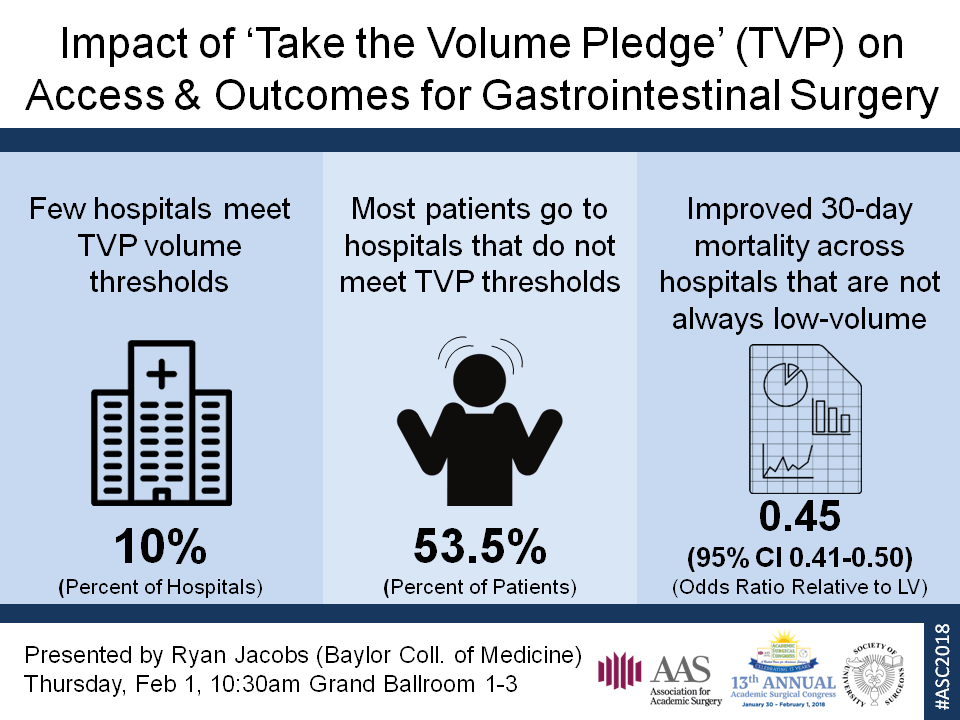

Introduction: The “Take the Volume Pledge” (TVP) initiative aims to regionalize complex cancer resections to hospitals meeting established annual volume thresholds. There is little data describing the potential impact on patient access if this initiative were broadly implemented or the relationship between TVP volume thresholds and quality of oncologic care.

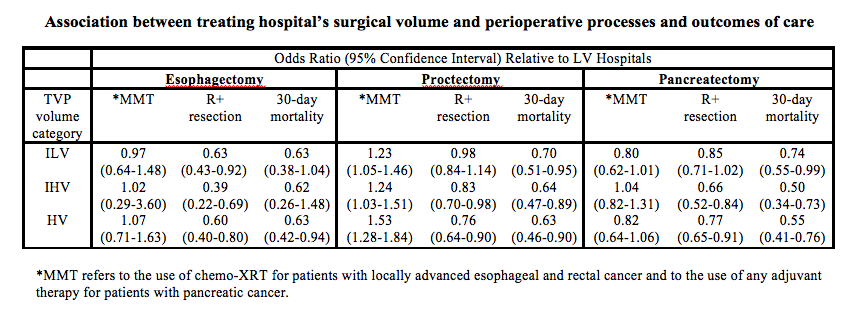

Methods: Hospitals performing esophagectomy (n=968), proctectomy (n=1,250), or pancreatectomy (n=1,068) in the National Cancer Data Base (2006-2012) were categorized into four groups based on frequency meeting TVP thresholds: always low volume (LV); low annual average and intermittently low volume (ILV); high annual average and intermittently high volume (IHV); always high volume (HV). Multivariable generalized estimating equations were used to evaluate the association between hospital TVP category and multimodality therapy (MMT) use, margin positive (R+) resection, and 30-day mortality.

Results: Over the study period, few hospitals met annual TVP thresholds (HV or IHV)—esophagectomy 1.6%; proctectomy 19.7%; pancreatectomy 6.6%. The majority of esophagectomy (77.8%) and pancreatectomy (53.4%) and 48.1% of proctectomy patients received care at hospitals not meeting annual TVP thresholds (LV or ILV). While unadjusted MMT, R+ resection, and 30-day mortality rates were better at ILV, IHV, and HV relative to LV hospitals, there were no consistent differences between non-LV (ILV, IHV, and HV) hospitals. The odds of receiving MMT was not different across TVP categories for esophagectomy or pancreatectomy (Table). For proctectomy, MMT use was significantly more likely (relative to LV hospitals) at ILV, IHV, and HV hospitals. For all three procedures, the odds of a R+ resection were lower (relative to LV hospitals) at IHV and HV hospitals (and at ILV hospitals for esophagectomy). However, there were no differences in R+ resection rates between ILV, IHV, and HV hospitals. The odds of 30-day mortality after esophagectomy was not different in any TVP category, except at HV (relative to LV) hospitals (OR 0.63 [0.42-0.94]). The odds of mortality were significantly lower (relative to LV hospitals) at ILV, IHV, and HV hospitals after proctectomy and pancreatectomy. But, there were no mortality differences comparing ILV, IHV, and HV hospitals.

Conclusion: Few hospitals meet TVP cancer resection volume thresholds with little difference in outcomes across non-LV hospitals. A policy to shift surgical care only to hospitals meeting TVP could compromise patient autonomy, limit access if patients are unable or unwilling to travel, and may not necessarily establish objective benchmarks for ensuring high-quality outcomes.