K. Kummerow Broman1,4, M. J. Ward2, B. K. Poulose1, M. L. Schwarze3 1Vanderbilt University Medical Center,General Surgery,Nashville, TN, USA 2Vanderbilt University Medical Center,Emergency Medicine,Nashville, TN, USA 3University Of Wisconsin,Vascular Surgery,Madison, WI, USA 4VA TN Valley Healthcare System,Geriatric Research And Education Clinical Center,Nashville, TN, USA

Introduction: Inter-hospital transfer is resource-intensive and can be burdensome for patients and families. Decisions regarding transfer can be particularly challenging for gravely ill surgical patients, for whom transfer may be arduous and of questionable clinical benefit.

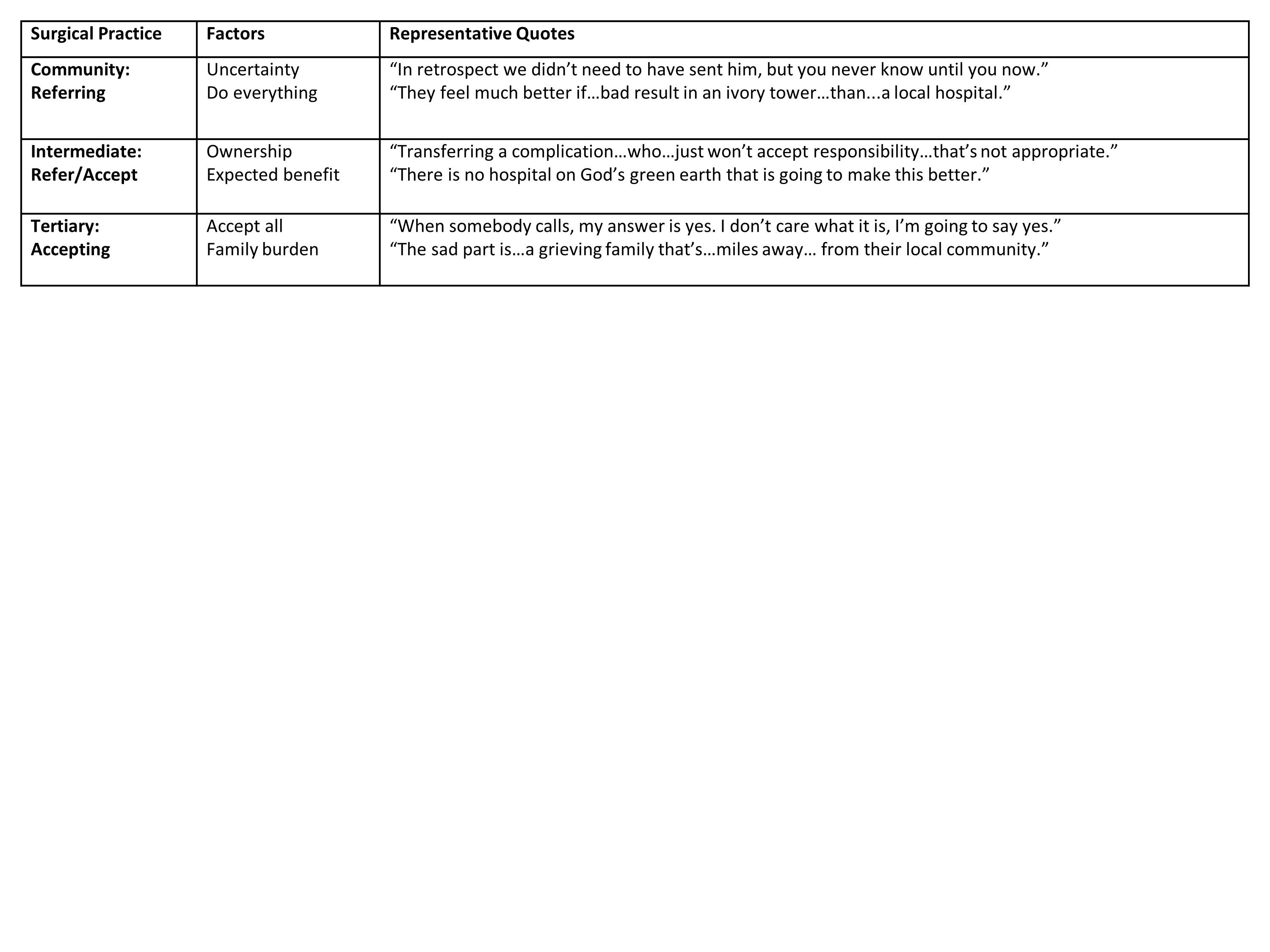

Methods: We conducted semi-structured interviews with general surgeons who refer and accept transfer patients within a regional transfer network. Participants were identified using a combination of snowball sampling, where initial study subjects were asked to identify additional subjects, and purposive sampling where respondents were selected deliberately to increase variability. Surgeons were selected from three community hospitals that refer patients, three regional hospitals that both refer and accept, and one tertiary referral center that accepts transfer patients. We completed 15 audio-recorded interviews that included open-ended questions and three case-based vignettes. Each interview transcript was analyzed by at least two members of the research team using a deductive coding strategy. We used consensus coding to generate higher level analysis about the content regarding surgeon transfer decisions for gravely ill patients with acute surgical problems.

Results:Referring surgeons seek transfer when they identify discordance between patient needs and local resources. When patients are gravely ill, transfer decisions are influenced by clinical uncertainty and a duty to exhaustively pursue treatment options based on surgeon judgement or family request. Accepting surgeons at regional facilities consider local resources, patient ownership, and expected benefit in their decisions to accept patients. Tertiary facility surgeons report a policy to accept all transfer patients based on a perceived responsibility to the region and difficulty making treatment recommendations without in-person assessment, but they express concern that dying patients may be unnecessarily transferred without survival benefit or adequate discussion of local palliative options. Palliative care and expertise in end-of-life communication may be uniquely available in higher level centers, although respondents were conflicted about the appropriate allocation of limited resources, specifically bed availability, for dying transfer patients.

Conclusion:Current policies and practices may fail to identify dying patients who will not benefit from transfer. Remote consultation, cultural shifts in end-of-life communication, and access to palliative care at community hospitals could provide needed support to surgeons, patients, and families while allocating scare tertiary care beds more judiciously.