L. E. Ward1, M. M. Padovany1, A. N. Bowder1,2, T. Jean-Baptiste1, R. Patterson1,3, C. M. Dodgion2 1Saint Boniface Hospital,General Surgery,Fond Des Blancs, , Haiti 2Medical College Of Wisconsin,General Surgery,Milwaukee, WI, USA 3Tufts University School Of Medicine,Boston, MA, USA

Introduction: It is estimated over 5 billion people lack access to surgery worldwide. This is often caused by a lack of surgical infrastructure and a paucity of surgical providers. St. Boniface Hospital (SBH), a 124-bed facility on Haiti’s southern peninsula, plays a critical role in providing safe, accessible surgery. SBH has grown its surgery program through three phases; Phase 1 (P1) general surgeries were performed by visiting surgical teams, Phase 2 (P2) general surgery was performed by a full-time surgeon in a single operating suite, Phase 3 (P3) the opening of a surgical center with three operating suites staffed by two general surgeons and surgical residents. We examine the impact of increasing surgical capacity at a rural hospital in Southern Haiti on case volume, patient complexity and mortality.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective review of all surgical cases performed on patients over the age of 18 at SBH between 2015 and 2017. Procedural data and patient demographics were recorded in operative logbooks at the time of the procedure. Postoperative mortality was defined by in-hospital deaths divided by the number of procedures performed.

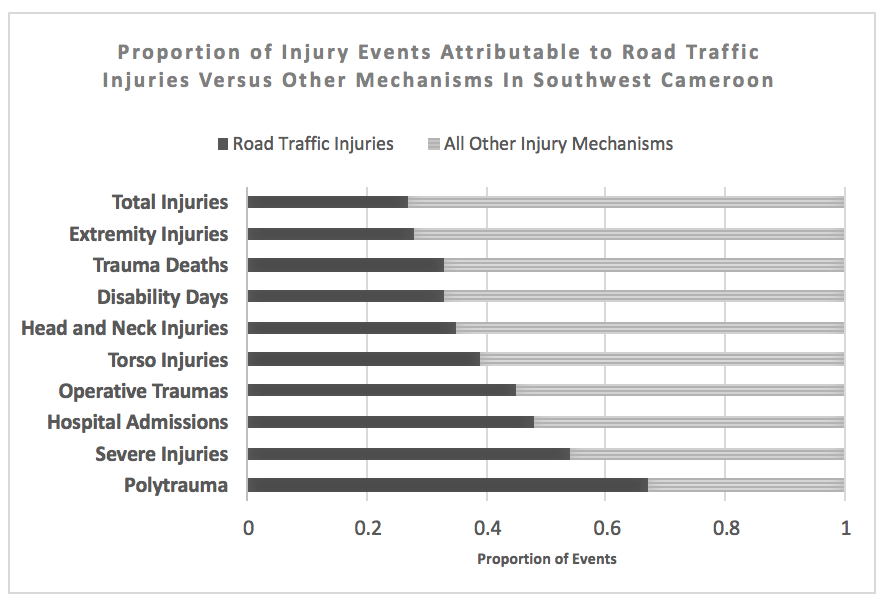

Results:1507 adult general surgical cases were done at SBH between February 2015 and August 2017. The volume of surgical procedures performed each month increased with stepwise growth in surgical capacity (Figure 1). The average number of surgeries per week were 3.1 with visiting surgical teams (P1), 10.4 with a single general surgeon (P2), and 20.1 with two full time surgeons and residents (P3). This represents a threefold increase in surgical volume between P1 and P2, and a twofold increase between P2 and P3. As the number of surgeries increased so did the complexity of patients. The percentage of patients with ASA scores of 1, 2, 3 and 4 during P2 was 81.3%, 17.3%, 4.2% and 1.0% respectively. In P3 the percentage of cases with an ASA score of 1,2,3, and 4 was 68.5%, 29.3%, 11.4%, and 1.3%. Surgical mortality during Phase 3 was 1.81% which compares favorably to to other surgical centers in Haiti.

Conclusion: Increasing resources and surgical staff at St. Boniface Hospital allowed for the greater delivery of safe surgical care. The increase in patient complexity represented by ASA scores suggests a greater referral base as a reputation was established. This study highlights the significant impact investments to improve surgical capacity can have in areas of great surgical need.